By Chris Robinson, Managing Director of RW Joinery

By Chris Robinson, Managing Director of RW Joinery

The specification of fire doorsets can seem daunting – particularly when ensuring the necessary certifications are in place to prove you have the right product for the job.

Thankfully, the days are gone when anyone claiming to manufacture fire doors could offer a global assessment and be done with it. Now, sensible clients and contractors ask for proof of manufacturers’ and installers’ competence, typically demonstrated through certifications such as BM Trada, IFC, or BlueSky. Additionally, technical associations like ADSMA are gaining the recognition they deserve for educating the market by providing good practice guides, lobbying parliament for better procedures, and explaining competence.

Some might say there’s almost a hysteria developing around fire door testing. Although opinion has changed positively, we now face challenges from those who are given a voice but do not always understand the details they demand.

The construction industry is acutely aware and increasingly vocal about tragedies like Grenfell and the need for better protection, especially regarding the suitability of fire door certification. Bona fide manufacturers and installers, like ourselves, have dogmatically spoken about the importance of certification for years, but there is confusion in the market that must be addressed.

Gaps in knowledge

Clients often request an individual burn test for each doorset combination we manufacture for their project. They want a different test for every size, vision panel layout, ironmongery combination and fire rating.

This issue is particularly prevalent in sectors such as housing, where fire doorsets are typically bespoke due to the multiple settings and requirements they must accommodate. Consequently, it can be tempting for facilities and maintenance professionals to ask for certification for every combination as a ‘belt and braces’ approach – but it’s wholly unnecessary and burdensome for all involved. Crucially, it’s also creating fear and uncertainty where there needn’t be.

In most instances, these requests are borne out of a lack of knowledge about fire door safety, testing and certification, and in some cases, due to contractors wrongly telling people that individual burn tests are required. Set against a backdrop of changing legislation – moving from BS 476 Part 22 fire-resistance testing to European EN test method EN 1634 in 2029 – and the impact of Grenfell, it’s perhaps easy to see how this problem has arisen.

Like many other manufacturers, we arrange and burn test doorsets each year, generally as a requirement of our certification processes or to achieve clients’ bespoke fire door requirements. This year, we decided to conduct the ultimate test by showing how many variances might be required in a single solution. We designed a 60-minute doorset that could be used in various ways to satisfy the demand for cross-corridor doorsets in public and private residences. The brief was simple: put all the combinations we’re asked for into one doorset. And so, the ugly doorset was born.

Meet the ugly door

The idea was to provide the ultimate proof that specifiers and facilities professionals require and to offer peace of mind regarding bespoke fire door testing. So, we manufactured the ugly doorset to include the following features:

- Glazed lower side panel

- Mid-rail with letter plate

- Glazed upper side panel

- Solid lower side panel

- Glazed over panel

- Extra wide door

- Extra height door

- Extra-large vision panel

- Inlaid beading to both faces of the door

- Offset (to stop reaching for keys) door letter plate

- Spy holes at standard and less abled heights

- Concealed door closer

- Face fix door closer

- Mortice lock access control

- Threshold smoke seal

- FD60 fire rating

- Smoke leakage control

- PAS24 (2016) certification

- Severe duty mechanical rating

We concluded that this would be the most onerous doorset we would ever test. However, our subsequent field of application would permit any combination of designs equal to or less than the tested ugly door.

The test

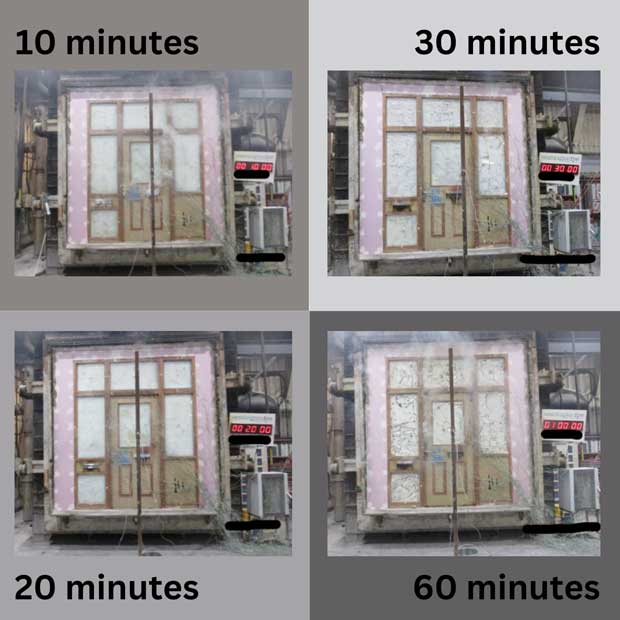

The performance of the ugly doorset was monitored and recorded at five key time points – 10, 20, 30, 60 and 70 minutes and the results were very telling.

At 10 minutes (see time stamp graphic), Smoke leaked through the letter plates as the heat had not yet fully activated the intumescent seals around them. This is acceptable. The intumescence within the glass had started activating, as demonstrated by the opaqueness.

At 20 minutes (see time stamp graphic), the intumescent seal within the letter plate had been activated, stopping the smoke leakage.

At 30 minutes (see time stamp graphic), the glass had started to crack but was held (as expected) in place by the intumescent interlayers.

At 60 minutes (see time stamp graphic) – The door passed the 60-minute test as the fire did not break through. There was some smoke penetration around the lock, letter plates and top corners of the door, which was to be expected. However, there was no smoke penetration below the door. Also, the inlaid bolection beading, a design feature we deliberately included to reduce the potential performance of the doorset, showed no deterioration despite the door being considerably thinner in this location. The glass had cracked, but the intumescent interlayers performed their job and kept it in place.

As the team was so intent on putting the ugly door through its paces, the test continued past the 60-minute mark. It endured 64 minutes before the first sign of failure, although the test wasn’t stopped until 70 minutes, with the door still holding. A 10 per cent overrun of six minutes would be considered excellent, so the ugly door succeeded. Despite its aesthetic challenges, the ugly door more than did its job.

Lessons learned

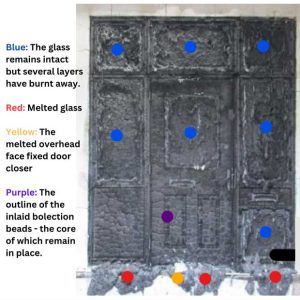

The side of the door exposed to the fire lived up to its ugly name at the end of the test. However, the images show the glass remained intact despite several layers burning away. Evidence of melted glass and the door closer were visible at the base of the doorset, and the outline of the inlaid bolection beads remained visible, too.

This exercise proves that excessive test evidence should not be required for every combination and that the elements most commonly requested are up to the job.

Thankfully, the ugly door will never be specified. It was not the intention. Its purpose was to assure facilities professionals, building managers, product specifiers and those with fire door responsibilities. The real takeaway from the ugly door project is that ultimate peace of mind comes from having up-to-date fire door knowledge and a partner willing to share their expertise and help clients make informed choices without fear, confusion, or unnecessary testing.